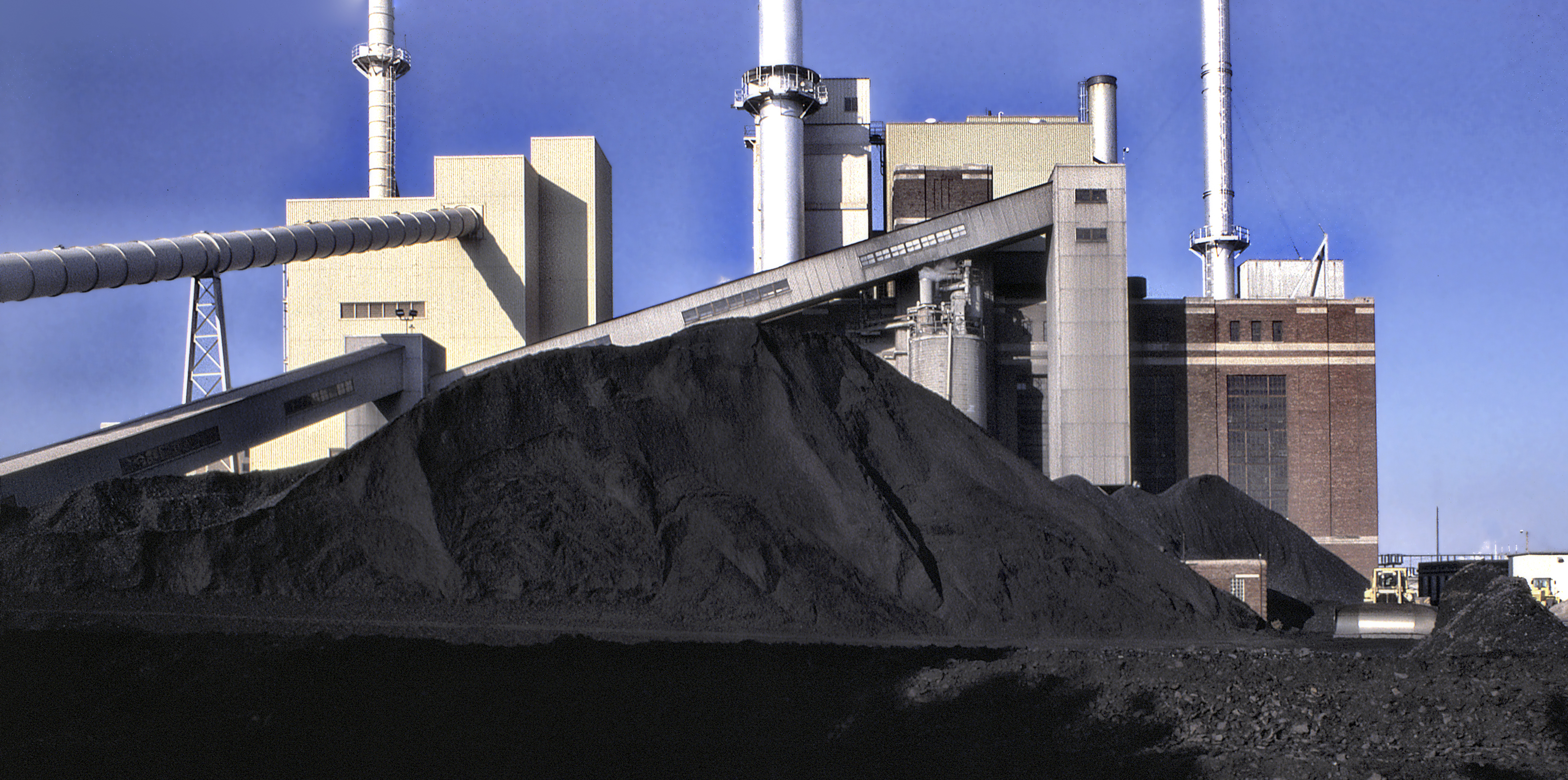

Fossil fuels are not only bad for the environment, they can be harmful to your physical well-being. This article by Co.Exist reports on the impact of polluted air and how the reduction in coal plants are improving human health and agriculture.

Between 2005 and 2016, hundreds of coal plants across the United States stopped operating, and that means millions of tons of carbon emissions have been prevented from entering our atmosphere. It’s also had a tangible impact on the nearby communities: with those coal plants decommissioned, and the pollution they once spewed into the air stopped, the abatement of the negative health effects from inhaling that pollution kept tens of thousands people alive.

Published in the journal Nature Sustainability, a University of California San Diego study looks at the effects we’re already seeing as the U.S. cuts its coal use. More than 330 coal-fired power generation units (one coal plant may contain multiple units) shut down across the country between 2005 and 2016, due in part to the aging of these facilities and the fact that other energy sources, such as natural gas, have become cheaper. We know that less coal is a good thing overall for our environment, but that doesn’t tell the full local story of what happens when we remove sources of pollution from specific areas.

“We talk about [pollution] like it’s a nebulous, everywhere burden that everyone shares equally,” says Jennifer Burney, associate professor of environmental science at UC San Diego and author of the paper. But what her findings make clear, she notes, is how drastically certain people are affected, based on their surroundings. When these plants burn coal, they release particulate matter that, when inhaled, has been linked to respiratory and cardiovascular hospitalizations, lung cancer, and stroke. So when they shut down, nearby residents inhale less of those pollutants, giving them longer lives. Because of cleaner air, an estimated 26,610 lives have been saved.

These pollutants also damage nearby plant life and can alter the immediate environment by blocking sunlight. Burney looked into the impact on local agriculture in places where coal plants shut down as well, and he found that the shutdown of these plants prevented a loss of 570 million bushels of corn, soybeans and wheat crops in the immediate surrounding areas.

To get to these numbers, Burney combined data from the Environmental Protection Agency and NASA to gauge changes in local pollution before and after coal plants shut down, and he also looked at county-level mortality rates and crop yield data from the Centers for Disease Control and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. “You have a bunch of really, in a scientific sense, natural experiments where all these old coal plants were places that went from having a lot of emissions to zero,” she says. “When they shut down, pollution lets up and ... You see that deaths go down and crops grow.”

The inverse calculation that shows the damage done by the coal-fired units still operating over that same time period – 738 units were online at the end of 2016, according to Burney, or 381 coal plants, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration – found that those online units caused 329,417 deaths from particulate matter inhalation, and 10.2 billion fewer bushels of crops, roughly equal to half of a recent year’s typical corn, wheat, and soy production in the U.S.

Burney says she was both surprised, and not surprised, by her findings. There have been a lot of public health studies that look at the mortality rate associated with pollution levels, and her findings are similar to these. Still, she adds, “Seeing these numbers in aggregate, it’s big.” Natural gas power plants have popped up across the country to replace these coal plants as an energy source, but natural gas also produces pollutants. “In this study, they don’t have the same association with death and crop yield, probably in part because they’re in more rural locations,” says Burney, but she thinks we still need to keep researching to understand those impacts better.

A lot of statistics around emissions are so broad, it can be difficult to wrap our heads around. What does it really mean that we reduced coal-based emissions 10% last year? What’s the real impact of cutting coal use, beyond its effect on our economy? “If you were going to ask anybody generally, ‘Do you want a policy that would save 1% of the population?’ they would say, ‘Hell yes,'” Burney says. She hopes her findings can help policy makers weigh the other costs of coal – that of human lives and crop production – when they consider building or decommissioning coal plants.

This article was written by Kristin Toussaint from Co. Exist and was legally licensed through the NewsCred publisher network. Please direct all licensing questions to legal@newscred.com.